|

Nature Geoscience published this very interesting editorial on the recent political controversy surrounding LOHAFEX.

The full text of the editorial is below:

The Law of the Sea

Abstract

In 2008

ocean iron fertilization was regulated under two sets of international

legislation. However, unclear definitions have led to the suspension of

legitimate research.

Introduction

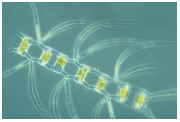

RICHARD CRAWFORD, ALFRED-WEGENER-INSTITUT

Base of the food chain: Antarctic phytoplankton. When

a marine research project is put on hold by the lead country's science

ministry, after the research vessel has already set sail, it is clear

that communication between scientists, the public and politicians has

gone seriously wrong. The suspension of the Indo–German iron

fertilization experiment LOHAFEX in January this year is a case in

point.

LOHAFEX (taken from loha, the Hindi word for

iron, and FEX, which stands for fertilization experiment) aims to study

the biogeochemical effects of iron fertilization in the South Atlantic

Ocean. Just when the research vessel was about to leave the port,

environmental groups protested against the experiment, arguing that the

experiment breached a May 2008 decision agreed on by the parties of the

United Nations convention on biodiversity. The decision restricts iron

fertilization to small-scale, scientific research studies within

coastal waters. The protests resulted in a two-week suspension of the

experiment, and left 48 scientists onboard the research vessel Polarstern wondering if they were sailing across the South Atlantic in vain.

By

early February, the research was back on track. The scientists had made

good use of the delay — identifying a suitable target eddy in the

region. The team required a stable eddy that contained plenty of

nutrients, but was low in productivity. This would allow the iron

addition to have a significant effect and provide a fairly closed

experimental system. So, when approval of the experiment came through

the iron was injected promptly, and has since stimulated the expected

plankton bloom. The fate of carbon in this system is now being

monitored as planned.

However, the controversy

leaves the scientists bruised, the environmental groups wondering

whether the UN's moratorium on iron fertilization will prevent

premature geoengineering, and the German Federal Environment Ministry —

whose support of the environmental protesters was instrumental in

achieving the experiment's suspension — unsatisfied.

The

rationale of the UN moratorium on ocean iron fertilization was to stop

the commercial companies who were getting ready to make money by adding

large amounts of iron to suitable regions of the ocean and selling

carbon credits in return (Science 318,

1368–1370; 2007). The UN convention on biodiversity decided that the

world is not yet ready for widespread fertilization efforts, certainly

not on an industrial-type scale: neither the capacity for carbon

capture nor the potential adverse effects are sufficiently understood

(see Nature Geosci. 1, 722–724; 2008) — an assessment most scientists would agree with.

The

January controversy has raged over the definitions of the terms of

exemption for scientific studies — 'small-scale' and 'coastal waters' —

which were not clarified in the text of the decision. Whether

fertilization of an ocean eddy with a surface area of around 300 km2,

as planned in the LOHAFEX experiment, can be classified as small-scale

is not straightforward, and a location hundreds of kilometres from the

nearest land mass is not obviously within coastal waters.

These

definitions must be seen in context. If the Southern Ocean were a

garden, the fertilized eddy would be the size of a daisy, as pointed

out by Karin Lochte — director of the Alfred-Wegener Institute for

Polar Research under whose flag the Polarstern is sailing — in an online newspaper report (http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/natur/0,1518,602984,00.html).

The project scientists argue that the water in their study region is

considerably influenced from land, by atmospheric deposits as well as

some constituents from the water, and can therefore be considered

coastal.

Whatever the answer, the row over

definitions is missing the point. At least the restriction to coastal

waters in the UN moratorium seems arbitrary. The London Convention and

Protocol, a legal body within the framework of the international Law of

the Sea, which regulates dumping and marine pollution, does not refer

to the terms 'small-scale' and 'coastal waters' in its October 2008

resolution on ocean fertilization. Instead, it distinguishes between

"legitimate scientific research", which is permitted, and "other

activities". As a result of both the chronology and the fact that the

international Law of the Sea takes legal priority over the UN

convention on biodiversity, this emphasis on legitimate science seems

more relevant.

The term 'legitimate', too, will need

further definition. Indeed, a working group of the London Convention

met in February with the aim of drafting more detailed regulations that

will make it easier to assess whether expeditions are scientifically

legitimate. However, there is little doubt that LOHAFEX passes this

criterion.

Given this situation, the question arises

as to why the research was held up in the first place. A press release

issued by the German Federal Environmental Ministry to express its

regret when the experiment was approved gives a clue. It states that in

its own view "attempting to halt climate change by interfering with our

marine ecosystems is a disastrous approach. This scientifically unsound

thinking has been a direct cause of the climate crisis and is in no way

suited to solving the problem." If this is the reason for condemning

LOHAFEX, then the statement seems to imply that ocean fertilization

(and, by extrapolation, other options of geoengineering) must not be

investigated at all.

But closing our eyes will not

make global warming go away. In case climate change continues we should

at least rule out scientifically, as early as we can, geoengineering

proposals that do not work — so that future generations do not go down

disastrous routes because there is no more time for detailed studies.

|